Centre needs to co-opt states to achieve its ambitious welfare goals by 2024

Follow us Now on Telegram ! Get daily 10 - 12 important updates on Business, Finance and Investment. Join our Telegram Channel

Follow us Now on Telegram ! Get daily 10 - 12 important updates on Business, Finance and Investment. Join our Telegram Channel https://t.me/InvestmentGuruIndia

Download Telegram App before Joining the Channel

NEW DELHI : When President Ram Nath Kovind set the tone for the Narendra Modi administration’s second term during his speech at a joint session of Parliament last June, he said in no uncertain terms how the goal of a $5-trillion economy can be achieved, in collaboration with states.

From sending a manned mission to space, using entirely indigenous resources, to playing a leadership role in global development and joining the world’s three largest economies, the President highlighted the need for co-opting states.

Now, the second Union budget of the Modi government’s second term on 1 February will be crucial, as it not only seeks to reverse an economic slowdown, but also to improve the living standards of the masses through better management of last-mile delivery of public goods. The ambitious welfare goals Modi has set for 2024 make it essential to have the unflinching backing of states, be it reforms or ensuring that the schemes deliver the desired results. Yet, mutual trust between the central and state administrations have frayed in recent months, making it evident that tackling some of the biggest challenges facing the country will not be easy.

The key goals the Centre has set for the next few years include water security and providing piped water to every rural home, developing more than 100,000 villages within the 100 most backward districts of India, building 35,000km of national highways in three years, building coastal and village roads, doubling the number of airports to 200, developing inland waterways and extending the rail network through private partnership. The moves are expected to make India more inclusive, while fuelling growth. The Union budget for FY21 is expected to reveal the Centre’s plan for achieving these targets, while focusing on regional priorities and financially supporting states. The budget will also reveal how much of its tax revenue the Centre will share with states, considering that the existing formula expires in March.

The two big challenges for states are the impact of climate change, resulting in floods and ruining crops, and the pressure of adding quality jobs, especially in times of a fund crunch—funding their social security programmes or other spending requirements to run a government.

State ministers, who met Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman last month for a pre-budget discussion, flagged the resource gap faced by states. Kerala, a coastal state that faces climate change challenges such as floods, rising sea levels and reducing land mass, wants a temporary relaxation in its borrowing power. Kerala’s finance minister Thomas Isaac said reconstruction and rehabilitation work since the worst floods in a century in 2018 is still on. “Rebuilding houses is almost complete. Village roads are being rebuilt. We needed about ₹30,000 crore. The GST Council had agreed that states that face natural calamity should be given a temporary increase in borrowing power," said Isaac in an interview.

The state levies a flood cess of 1% on the value of goods and services at the retail level to fund the reconstruction work. Some states, including Kerala, demanded that the Centre raise the cap on their borrowing from 3% of gross state domestic product (GSDP) so that they can allocate more funds for development. Haryana chief minister Manohar Lal Khattar sought the Centre’s assistance for its pension scheme, rail and metro rail expansion, and to scale its crop residue burning programme.

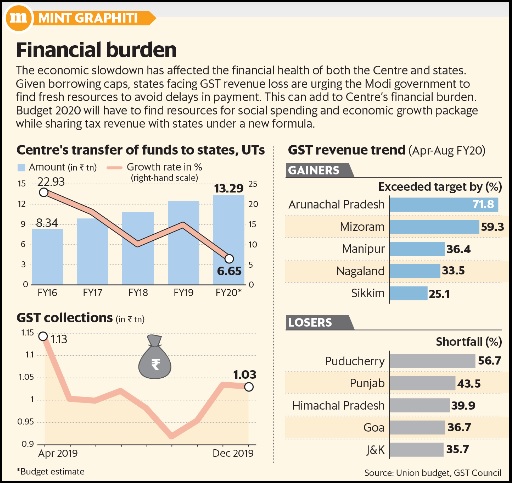

Experts said there was a case to reconsider the existing formula on the central government’s transfer of resources to states. In line with the 14th Finance Commission’s advice, the Centre has raised the tax revenue it shares with states by 10 percentage points to 42%, enhancing the financial autonomy of the states and helping them prioritize their social sector spending. However, several states said that simultaneously there was a reduction in the government’s support for centrally-sponsored schemes.

“While there is one view that states may need to be given more flexibility, it is not necessary that all states are on a par. There is some handholding that the Union government needs to do, both in terms of expertise and financial support. I think there is a need to re-look at the recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission to step up central intervention in the social sector," said N.R. Bhanumurthy, professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, a think tank. The FFC’s recommendations for FY21 will also get reflected in the budget.

The economic slowdown has played havoc with the revenue projections of the central and state governments, straining their relations. This has forced many states to go public with their disappointments on delays in payment of GST compensation dues by the Modi administration.

320-x-100_uti_gold.jpg" alt="Advertisement">

320-x-100_uti_gold.jpg" alt="Advertisement">