High Yields: A Potential Fault Line for Debt Dynamics of Advanced Economies by CareEdge Ratings

Executive Summary

Advanced Economies have had elevated public debt for two decades now. What has changed more recently is the cost of carrying this debt. In previous episodes of high debt, advanced economies benefited from low borrowing costs, which helped contain debt servicing pressures following the global financial crisis.

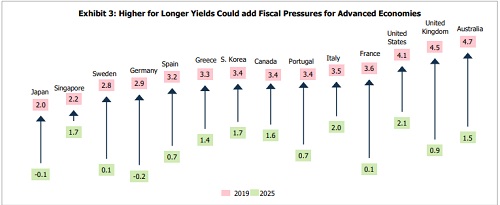

As economies pursued monetary tightening in 2022 to address the inflationary pressures, yields rose across most of the advanced economies. Most countries have entered easing cycles since then; however, it has not translated into a meaningful decline in long-term sovereign yields. These persistently high yields reflect underlying fiscal concerns faced by advanced economies.

Fiscal pressures are increasingly shaped by a combination of structural and cyclical rigidities, as reflected in widening primary deficits. This is primarily due to four reasons:

* Demographic pressures: Most of these economies are facing an unfavourable demographic transition, which has added to fiscal pressures through ageing-related expenditures and persistently rising healthcare costs.

* Growth concerns: Additionally, medium-term growth prospects could be weighed down by an external environment shaped by geopolitical tensions, trade fragmentation, and prolonged uncertainty.

* Higher defence spending: Further, higher defence and security-related spending, driven by geopolitical tensions that are no longer episodic, carries tangible fiscal costs.

* Inability to implement reforms: Meanwhile, the institutional capacity to manage these fiscal and economic headwinds has weakened due to political fragmentation and declining institutional strength. This has reduced policymakers’ capacity to manage an increasingly expansionary fiscal stance without undermining fiscal credibility

The confluence of these challenges has begun to feed into market concerns over future debt dynamics. Consequently, despite the ongoing cycle of policy rate easing, sovereign yields remain elevated relative to their earlier lows.

As these higher borrowing costs coincide with subdued growth, interest–growth differential (r–g), an important metric of debt sustainability, is also expected to turn relatively less favourable across most advanced economies. This could reduce the ability of (r–g) to partly or fully offset primary deficits, placing upward pressure on debt ratios, particularly in the context of widening fiscal deficit.

The consequences will not be uniform. There could be differential implications for advanced economies due to differences in their economic structure, growth potential and institutional strength. Further, policy credibility for each country will matter more than ever in determining how individual advanced economies navigate this new environment.

Yields Expected to Remain Higher for Longer

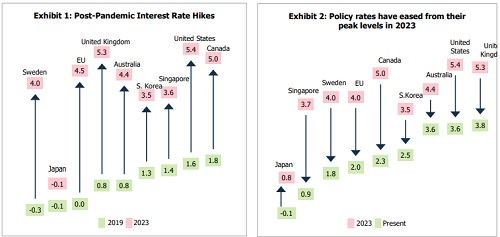

Sovereign borrowing costs across advanced economies have entered a structurally higher regime. Even as central banks have begun easing policy after the post-2022 tightening cycle (Exhibit 1 & 2), long-term sovereign yields remain elevated relative to pre-pandemic norms. This persistence signals a deeper shift in market pricing. Yields are no longer anchored primarily by expectations of policy rates, but increasingly by concerns over fiscal sustainability, growth capacity, and institutional resilience.

Despite this, markets are reassessing the ability of advanced economies to carry high public debt in a world of slower growth, rigid spending structures, and rising structural risks. The result is a higher risk premium embedded in long-dated sovereign debt, keeping yields higher for longer (Exhibit 3).

The Drivers Behind Persistently Elevated Yields

a) Fiscal challenges prolong for advanced economies (rigid spending & elevated debt levels) Rigid Spending: A defining fiscal challenge for advanced economies is the growing rigidity of their public spending. Unfavourable demographic trends lie at the core of this shift. Since the early 2010s, the share of the population aged 65 and above has risen sharply, pushing many economies from being ‘aged’ into ‘super-aged’ demographic categories.1

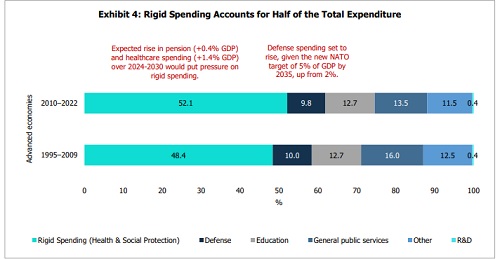

Exhibit 4 shows that inflexible spending has accounted for around half of total expenditure for nearly two decades, highlighting the persistence of fiscal rigidities. These pressures have intensified since the pandemic, as support measures for households and firms have been difficult to unwind, keeping subsidies elevated and public-sector wage bills sticky. As a result, spending in advanced economies has tilted further toward non-discretionary items, particularly health and social expenditure. This persistence suggests that underlying structural pressures are unlikely to ease materially in the near term, and even modest increases in non-discretionary spending can erode fiscal flexibility during economic downturns

National authorities have also highlighted rising rigid expenditure pressures amid ageing populations.

* For instance, in France, the public audit office has issued a warning regarding the high healthcare, pensions and elderly support costs that could absorb more than 40% of public spending and push overall outlays above pandemic-era highs without reforms.

* Similarly, the Central bank of Germany (Bundesbank) has highlighted the mounting fiscal strain from pension commitments and an ageing workforce, noting that recent policy adjustments are unlikely to alleviate long-term budgetary pressures sufficiently. This dominance of rigid, consumption-oriented spending is expected to further crowd out the momentum for private investment. With the rising share of rigid spending in total expenditure in advanced economies, productivity-enhancing public expenditure, such as infrastructure, education, and innovation, has been increasingly constrained.

High Debt: In addition to expenditure rigidities, elevated debt levels are intensifying fiscal pressures. Advanced-economy public debt stood at 109.1% of GDP in 2024 and is projected to rise to around 120% by 2030, approaching pandemic-era peaks. Given that advanced economies account for nearly 60% of global sovereign debt, the scale of their indebtedness carries significant global implications.

Above views are of the author and not of the website kindly read disclaimer