Great Indian Family doesn`t help working women

Follow us Now on Telegram ! Get daily 10 - 12 important updates on Business, Finance and Investment. Join our Telegram Channel

https://t.me/InvestmentGuruIndiacom

Download Telegram App before Joining the Channel

Now Get InvestmentGuruIndia.com news on WhatsApp. Click Here To Know More

Domestic duties including childcare might be keeping many Indian women from working but living with the in-laws does not mean that women are more able to take up jobs, new research indicates. On the contrary, women who live in joint families are significantly less likely to participate in the labour market.

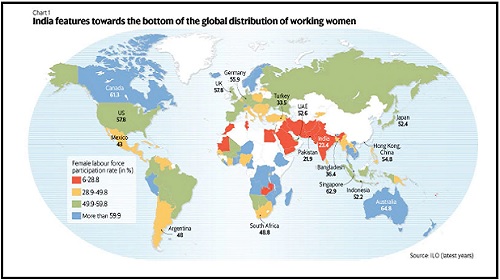

India has some of the lowest levels of female labour force participation in the world. Fewer than a quarter of adult women (23.4%) reported working or being available for paid work in the 2011-12 National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) survey on unemployment.

According to leaked portions of the 2017-18 report published by Business Standard, this share fell even further. Of the 149 countries for which the International Labour Organization (ILO) has comparable data, only 10 countries have a lower share of women in the paid workforce than India.

suggests that the declining participation of women in the job market has several causes—from higher enrolments in higher education to rising household incomes to occupational segregation restricting job opportunities for women. The lack of childcare exacerbates the problem.

According to ILO data, Indian men shoulder less than 10% of the burden of unpaid housework in terms of time spent (an average of 31 minutes), among the lowest in the world. However, that comparison is based on India’s last time use survey which was in 1998-99, and there is no more recent comparable data. Other, more recent data sources buttress the fact that domestic work and childcare still restrict women from taking up paid work.

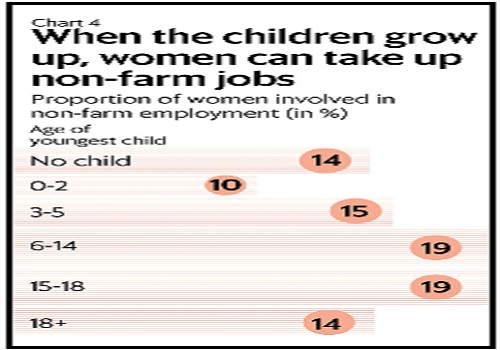

According to more recent data from the National Family Health Survey and the National Sample Survey Office, the presence of children aged 0-5 is a strong predictor of dropping out of paid work. The primary reason that women engaged in “domestic duties" (including childcare) gave to NSSO surveyors in 2011-12 for not being part of the workforce was that there was no one else to carry out their domestic duties.

Then, would living in a joint family, where typically grandparents reside, provide the childcare that frees women to pursue paid work? Researchers Sowmya Dhanaraj of the Madras School of Economics and Vidya Mahambare of the Great Lakes Institute of Management, Chennai, found that this is not the case.

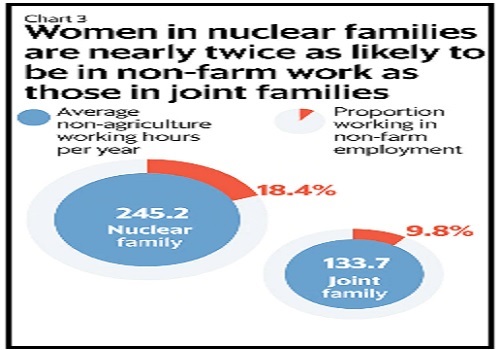

Using data from two rounds of the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) conducted by the National Council for Applied Economic Research and the University of Maryland, they found that residing in a joint family reduces rural women’s participation in non-farm employment by more than 10 percentage points, and that this was mainly through the restriction of women’s “decision-making authority and mobility within and outside the household". (read more)

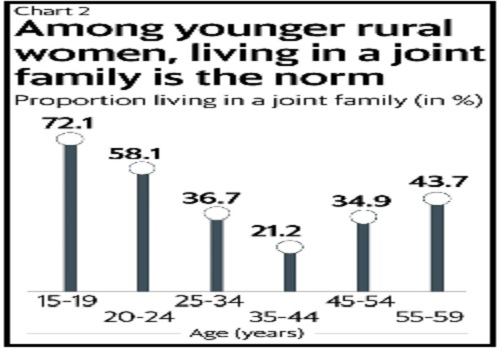

Newly married couples typically tend to live with one or more married couples usually the man’s parentsand may then move to live independently when they face a lack of space or migrate for work, data from the IHDS indicates. On average, 34% of rural women live in joint families.

Non-farm employment rates for women from joint families lag substantially behind those for women in nuclear households. Such work typically involves leaving the house and working among people other than one’s family, and the rates of non-farm employment are lower for women from joint families in all education categories, narrowing only for tertiary education levels.

The researchers also find that women from upper caste groups are more likely to reside in a joint family system than those from disadvantaged groups. The higher social status associated with being upper caste acts as an inhibitor for ‘allowing’ women to leave the house for paid work, other research has also shown. Joint families in the IHDS sample are also associated with restrictions on decision-making ability and mobility.

There is no real evidence of a joint family offering childcare. The difference in proportion of women working in non-farm employment between joint and nuclear families only decreases for older women when the children have grown up.

These findings from India are in stark contrast with evidence from countries such as China, where residence in a joint family raises the likelihood of a young woman moving into formal employment.

In countries such as Canada, expanded access to subsidised professional childcare allowed substantially more women to access education and employment.

What factors help women access non-farm employment? The researchers find that education has a significant impact—a greater proportion of women with secondary or tertiary education who live in a joint family work in non-farm jobs compared to women with low education.

They also find that being in a joint family has lesser consequences on women’s employment in southern states than in northern states.

In villages with better access to roads and greater availability of jobs in Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, more rural women are available to work outside farms, the research suggests.